The Ballets Russes… Firebirds, Fauns and Fighting

Much of the 20th century orchestral music that today dominates concert halls and recording studios started as music for ballets. And the best of it started with the Ballets Russes company; which was largely the creation of one man… the Russian impresario Sergei Diaghilev. It is hard to think of another instance where one man, who was not a composer, has had such an outsize influence on what has come down to us as great and lasting music. And I’m going to play you a selection of that music… from Nicolai Rimsky-Korsakov, Igor Stravinsky, Claude Debussy, Maurice Ravel, Erik Satie, Manuel de Falla and Sergei Prokofiev… as well as giving you a little of the Diaghilev and Ballets Russes story.

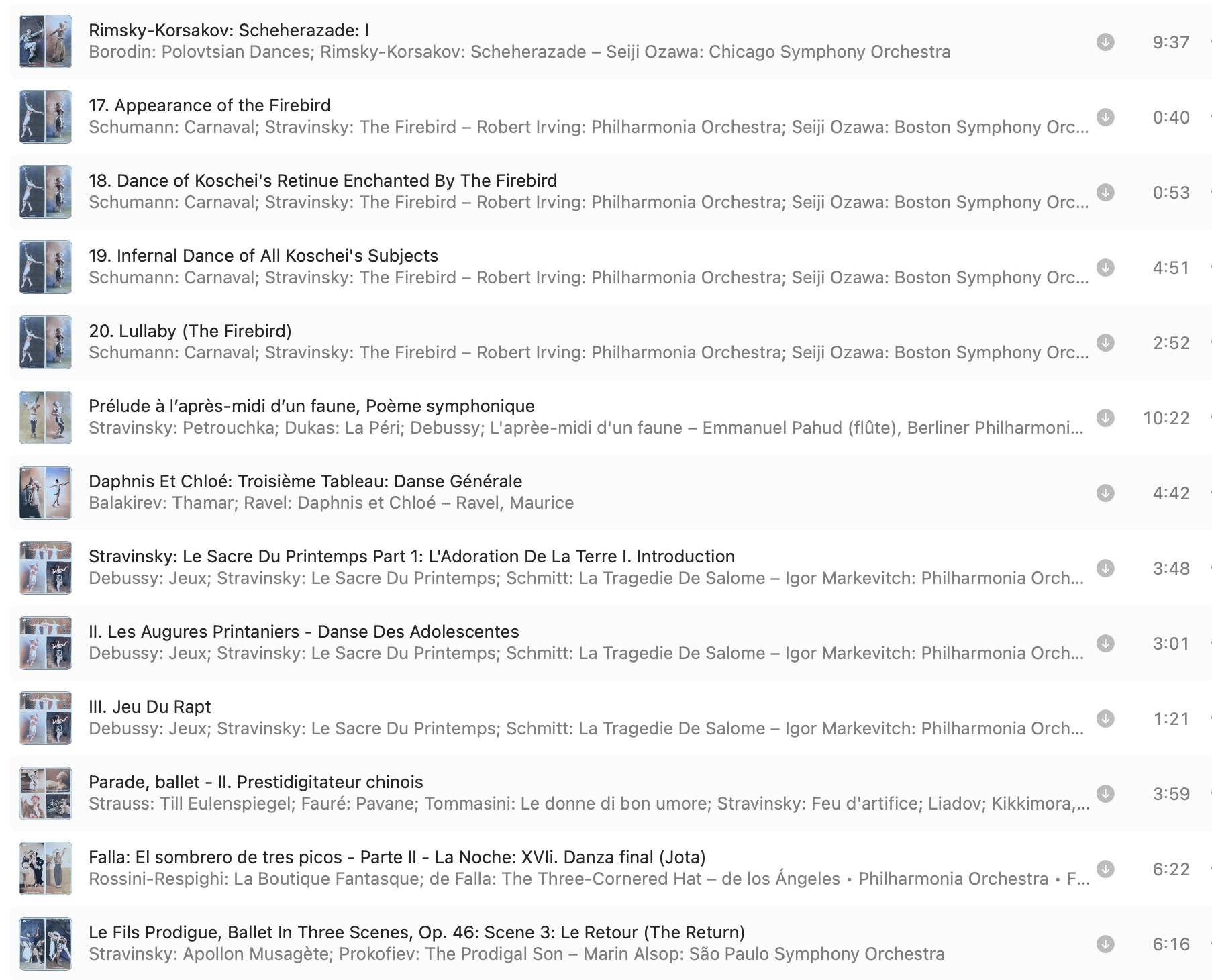

And here is a link to a playlist on Spotify with the music from this episode:

https://open.spotify.com/playlist/7vARdUO92MYS4RknQ7cQqZ?si=3db266eff3ee4098

The Music

The Words

Hello everyone. Welcome to another episode of the ‘Classical For Everyone’ Podcast… five hundred years of incredible music. My name is Peter Cudlipp and… If you enjoy any music at all then I’m convinced you can enjoy classical music. All you need are ears. No expertise is necessary. If you’ve ever been curious about classical music… or explored it for a while once upon a time… or just quietly wondered what all the fuss was about… then this is the podcast for you.

And because there’s a lot of music out there each episode has something of a theme. And for this one it is… music that was either commissioned for or popularised by, a ballet company based in Paris from 1909 to 1929… called the Ballets Russes.

Much of the 20th century orchestral music that today dominates concert halls and recording studios started as ballet music. And frankly the best of it started with the Ballets Russes company, which was largely the creation of one man… the Russian impresario Sergei Diaghilev.

It is hard to think of another instance where one man, who was not a composer, has had such an outsize influence on what has come down to us as great and lasting music. And I’m going to play you a selection of that music… from Nicolai Rimsky-Korsakov, Igor Stravinsky, Claude Debussy, Maurice Ravel, Erik Satie, Manuel de Falla and Sergei Prokofiev… as well as giving you a little of the Diaghilev and Ballets Russes story.

Now ordinarily I would try to avoid using a title in a foreign language but the French term ‘ballets russes’ translates to the not very useful ‘russian ballets’ which could lead to some confusing sentences like ‘the next ballet in the 1911 season of the Russian ballets was a Russian ballet. So, Ballets Russes it is.

The company is most famous today for the music Diaghilev commissioned and I’ll come to that but for the first two seasons most of the ballets were choreographed to existing music, most of it from Russia. And in 1910 the company took Nicolai Rimsky-Korsakov’s 1888 musical exploration of oriental folk tales, Scheherazade, and created a ballet from it.

Now the Scheherazade music would probably have had something of an ongoing life even if not for the ballet but this production transformed it from a respected orchestral suite into a cultural phenomenon. It was breathtaking in its daring and eroticism. Michel Fokine's choreography, the company’s principal dancer Vaslav Nijinsky painted entirely in gold seducing the Sultan’s favourite wife danced by Ida Rubinstein… plus Leon Bakst's opulent oriental designs made Scheherazade scandalous and irresistible in a way concert performances never could.

Here is the opening section of Scheherazade, ‘The Sea and Sinbad’s Ship’. It is about nine minutes long and is performed here by Seiji Ozawa conducting the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. Even though Rimsky-Korsakov never intended his music to be for ballet, and actually didn’t even like ballet, it is I think kind of hard now not to hear it as a score to be danced to.

A

That was the opening section of Rimsky-Korsakov’s Scheherazade, ‘The Sea and Sinbad’s Ship’ performed by Seiji Ozawa conducting the Chicago Symphony Orchestra.

Ok. For the next few minutes I’m going to give you a little of the origin story of Sergei Diaghilev and his Ballet Russes.

Diaghilev was born in 1872. He studied law in St. Petersburg in Russia but gravitated toward the arts, becoming part of a circle of young intellectuals who founded the journal ‘World of Art’ in 1898. Diaghilev proved himself a brilliant impresario rather than a creator - he couldn't compose, couldn't paint, couldn't dance - but he had an extraordinary eye for talent and a genius for bringing artists together. The other incredible gift Diaghilev had was finding other people’s money. What money his minor aristocracy family had, they lost when Diaghilev was young. But throughout his life he and his company were supported by wealthy patrons.

In 1906 he organized a massive exhibition of Russian art in Paris, introducing Western Europe to icons, Russian modernism, and everything in between. The exhibition was a sensation, and the following year he brought Russian opera to Paris. And in 1909 he founded the Ballets Russes and presented the first season.

From even before the time of the ‘World Of Art’ journal, Diaghilev was frankly obsessed with bringing what he saw as the primitive, youthful and exotic energies of Russian art, and in particular Russian folk art to the fading cultures of the West… almost as some sort of transfusion of Russian vibrancy into the sclerotic veins of old Europe.

In late 1909 Diaghilev decided it was time for the company to create a ballet from scratch and a story based on Russian folk and fairy tales was drawn together by a sort of committee from Diaghilev’s circle including the choreographer Michel Fokine and designer Leon Bakst of Scheherazade fame along with artist Alexandre Benois and others. They called it ‘The Firebird’. Now all they needed was some music.

After considering several candidates Diaghilev wrote to the composer Anatoly Lyadov saying…

“I need a ballet and a Russian one – the first Russian ballet, since there is no such thing. There is Russian opera, Russian symphony, Russian dance, Russian rhythm – but no Russian ballet. And that is precisely what I need – to perform in May of the coming year in the Paris Grand Opera and in the huge Royal Drury Lane Theatre in London. The libretto is ready. It was dreamed up by us all collectively. It is The Firebird.”

Who was Anatoly Lyadov you might be asking? Well, he was an established Russian composer and teacher who had already done some orchestrations for Diaghilev but he was a slow worker and intensely self-critical. At some point , and the information is vague, Diaghilev decided that the deadline for the ballet was not going to be met. And that he needed another composer.

He turned to the unknown 27 year-old Igor Stravinsky two of whose works he had heard at a concert in St Petersburg earlier in the year. He had then given him a small job orchestrating two Chopin pieces… about ten minutes of music.

The Firebird, and Stravinsky’s next two ballets for Diaghilev, ‘Petrushka’ and ‘The Rite of Spring’ would become as close to household names as any pieces of modern classical music ever have. But back then betting on the unknown and untried Stravinsky must perhaps have seemed a huge roll of the dice by Diaghilev.

Here is a little under ten minutes from ‘The Firebird’ including the ‘Infernal Dance’ section. Again the conductor is Seiji Ozawa but this time it is the Boston Symphony Orchestra.

B

That was a section of Igor Stravinsky’s music for the Ballets Russes ‘The Firebird’ from 1910. The conductor was Seiji Ozawa with the Boston Symphony Orchestra.

So, in the two pieces I’ve played so far I’ve hopefully given you the sense that the Ballets Russes was breathing new life into existing works from Russia as well as creating entirely new works that would change musical language forever.

But there is another important aspect of the story that is worth mentioning. In some instances the combination of a known piece of music and a particular dancer was enough to create a sensation and elevate the music of the ballet to the level of a modern classic. Such was the case when in the 1912 season Diaghilev programmed a ballet to Claude Debussy’s ‘Prelude to the afternoon of a Faun’ with choreography, and the role of the faun danced by, Vaslav Nijinsky.

With the ten minutes of music Debussy made an impressionistic version of a poem by Stephane Mallarmé about a faun, a half goat half man from Greek mythology, waking from a dream of frolicking with several nymphs in the afternoon in their arcadian meadows.

The erotic overtones in the original poem are somewhat understated and there is perhaps a certain sensuality to the music …but, based on the reactions to the first performances, Nijinsky as the faun, costumed in a body suit with piebald patches of animal skin, a short tail, a belt of vine leaves and horns sprouting from his head, chasing six beautiful young nymphs in ultimately unfulfilled lust made an extraordinary and lasting impression.

And I think this performance and the revivals that have followed over the last century and a bit are what has made this music, beautiful as it is, the central work it has become.

Here with Claude Debussy’s ‘Prelude a l’après-midi d’un faune’ ‘Prelude for the afternoon of a faun’ is the Berlin Philharmonic conducted by Simon Rattle and the solo flute is played by Emmanuel Pahud.

C

That was Claude Debussy’s ‘Prelude for the afternoon of a faun’. The Berlin Philharmonic was conducted by Simon Rattle and the solo flute was played by Emmanuel Pahud.

The Ballets Russes was probably always on the brink of financial collapse but that doesn’t seem to have dampened Diaghilev’s ambitions. And from 1910 on his focus became more and more on the creation of entirely new ballets as a major part of each season. And this led to a series of musical works which, once launched successfully as ballets, went on to become central to concert halls, radio broadcasts and recording studios… including Daphnis and Chloé by Maurice Ravel from the 1912 season.

From a 21st century perspective it’s hard to quite comprehend the central place ancient Greek and Roman characters, scenes and myths had in the artistic expressions of belle-epoque Paris. But if you look at the ballets leading up to the First World War, there are quite a lot of nymphs, shepherds, sacred woods and fauns.

Daphnis and Chloé ends with the shepherd and shepherdess after whom the ballet is named reunited and surrounded by shepherdesses dancing wildly in tribute to the god Pan and his beloved nymph Syrinx.

Here is that concluding section. It is about five minutes long and this recording is of Jean Martinon conducting the Orchestra of Paris.

D

That was Jean Martinon conducting the Orchestra of Paris with the concluding section of Maurice Ravel's music to the ballet ‘Daphnis et Chloé’.

I gave this episode the subtitle Firebirds, Fauns and Fighting. We’ve had a firebird and a few fauns. Time for some fighting. Igor Stravinsky followed The Firebird with Petrushka, another wonderful work that I am going to unfairly skip over to get to his ‘The Rite Of Spring’ which premiered by the Ballets Russes on the night of 29thMay 1913.

At that performance a riot, or a near riot or a series of scuffles broke out. Punches were thrown, people were hurt. A bunch of police arrived. The reports and the later reminiscences are contradictory but for the purposes of this podcast, I think we can call it a fight. Why were people fighting? The simplest description I have read is that the audience was polarised between an older conservative group who hated the music and perhaps even more the choreography by Vaslav Nijinsky that seems to have been more about stomping than dancing, and a younger group thrilled by the challenge and demands of Stravinsky’s continuing drift into harsh and jarring harmonies and dazzlingly complicated rhythms.

Another factor that divided the reactions may have been the dark and disturbing premise of the ballet’s story… A pre-Christian Russian tribe gathers to appease the pagan gods by sacrificing a young woman… who, once chosen by the old men of the village, dances herself to death. This will guarantee a bounteous Spring.

Perhaps keep that in mind as you listen to the opening eight minutes of Igor Stravinsky’s music for the ballet ‘Le Sacre du printemps’ or ‘The Rite of Spring’. Igor Markevich conducts the Philharmonia orchestra.

E

That was the opening eight minutes of Igor Stravinsky’s music for the ballet ‘The Rite of Spring’. Igor Markevich conducted the Philharmonia orchestra.

Another part of the Ballets Russes story is that Diaghilev’s company became a magnet for great European artists of that time. I think the next ballet I’m going to play you some music from is a good example. It is called ‘Parade’. The music was written by Erik Satie, the story was by Jean Cocteau. Pablo Picasso did the set design and the costumes. Incidentally two other significant figures who worked with the company were Henri Matisse and Coco Chanel.

The plot of Parade follows a varied group of sideshow performers and circus acts trying to attract an audience for their shows and it has, what was for the time, a deliberately low-brow setting... the streets of Paris. No nymphs or goddesses.

And whilst the fights at the opening of The Rite of Spring are justifiably famous another fight stemming from Parade is just a footnote but it is worth telling the story. Receiving a bad review from the music critic Jean Poueigh, Satie sent him a post card reading ‘Monsieur et cher ami – vous êtes un cul, un cul sans musique! ("Sir and dear friend – you are an arse, an arse without music!) The critic sued Satie and won. Satie was sentenced to eight days in jail. And apparently at the trial Jean Cocteau was arrested and beaten by police for repeatedly yelling out "arse" in the courtroom. Which I can’t imagine helped Satie's case.

Some music. Here is the section called ‘The Chinese Magician’ from Erik Satie’s music for the ballet Parade from the 1917 season of the Ballets Russes company. It is about four minutes long and Michel Plasson conducts the Toulouse Capitole Orchestra.

F

That was the section called ‘The Chinese Magician’ from Erik Satie’s music for the ballet Parade. Michel Plasson conducted the Toulouse Capitole Orchestra.

Somehow the Ballets Russes continued operating through the catastrophe of World War One but the annual returns to Russia and the frequent exchange of dancers between St Petersburg and Paris were blocked by the killing fields snaking through Europe from the Baltic to the Mediterranean. Diaghilev adapted. In 1916 two tours took place. Half the company led by Nijinsky went to the US for the second time and the other half including Diaghilev and Stravinsky went to Spain.

And on that tour Stravinsky introduced Diaghilev to the composer Manuel de Falla, and he was captivated by de Falla’s music which drew inspiration from the dances and melodies of ‘Al-Andalucia’… Southern Spain. The following year they would tour the area together as de Falla worked on the ballet Diaghilev commissioned.

It was called ‘El sombrero de tres picos’ which in French was ‘Le tricorne’ the title used for its runs in London and Paris. Sadly when translated into English it is ‘The Three Cornered Hat’ which frankly sounds like a children's book title, not a sexy, flamenco-infused ballet about a lecherous magistrate chasing a miller’s faithful wife. Even with that handicap the music from the ballet is the best known work by Manuel de Falla. In fact without Diaghilev’s commission and the impact of Picasso’s costumes and set designs for the first production, I wonder if de Falla’s name would be known outside Spain at all in the 21st century?

And in case you are wondering, the plot of the ballet which is ultimately something of a comedy includes deceptions involving the Magistrate and the Miller stealing each other’s clothes and the Magistrate’s three cornered hat is a symbol of class and power difference as well as being an effective stage device to indicate the character disguises. As well as being a literal badge of office in the 18th century when the ballet is set. Hence the title.

Here is the final six minute dance. It is the Philharmonia Orchestra conducted by Rafael Frühbeck de Burgos. Manuel de Falla’s ‘The Three Cornered Hat’.

G

That was the Philharmonia Orchestra conducted by Rafael Frühbeck de Burgos with the final dance from Manuel de Falla’s ‘The Three Cornered Hat’.

My name is Peter Cudlipp and you have been listening to the ‘Classical for Everyone’ Podcast. I have one final piece coming up but before I get to it I want to give you a little information that I hope you find useful… If you would like to listen to past episodes… or get details of the music I’ve played please head to the website classicalforeveryone.net. That address again is classicalforeveryone.net. And on the individual episode pages of the website there are links to Spotify playlists with the full versions of most of the music played in each of the episodes.

I hope you have enjoyed this Ballets Russes episode of ‘Classical For Everyone’. If you want to make sure you don’t miss the shows as they are released then please Subscribe or Follow wherever you get your podcasts. And if you want to get in touch then you can email… info@classicalforeveryone.net.

I’m afraid this has been one of the longer episodes of the podcast but there is just so much material. I’ll try to give you a quick conclusion. Diaghilev died in 1929 effectively ending the 20 year story of the Ballets Russes. Except that various offshoots borrowing the name kept something of the tradition going… there were the Ballets Russes of Monte Carlo and I think a rival company called ‘The Original Ballets Russes’ and several more. But more importantly the choreographers and dancers from Diaghilev’s Ballet Russes over the following years and decades took these ballets and what had now become traditions, with them around the globe.

And I mean around the Globe. In the late 1930s versions of the Ballets Russes toured Australia three times and several of the dancers ended up settling there. The Czech dancer Edouard Borovansky started a school and company in Melbourne and the Swedish dancer Helene Kirsova started a company in Sydney. Their traditions going back to Nijinsky and Fokine would be passed on to dancers who would then form the Australian Ballet in 1962.

But perhaps the best known legacy of the Ballets Russes was that of the dancer and choreographer George Balanchine. A graduate of the Imperial Ballet school of St Petersburg he was invited by Diaghilev at the age of 21 to join the Ballets Russes and was for five years the company’s principal choreographer. After Diaghilev’s death a wealthy patron from New York invited him to move to the US. He started ballet school in 1934 and in 1948 he founded the New York City Ballet which he led for 35 years and through which he became essentially the father of American ballet.

One of the last ballets Diaghilev presented was called ‘The Prodigal Son’ and the music was by Sergei Prokofiev. George Balanchine was the choreographer. Getting back for a second to the ongoing influence of the Ballets Russes, when Balanchine revived The Prodigal Son in New York in 1950 the lead dancer was Jerome Robbins… who would go on to a pretty good career of his own… including the creation of West Side Story.

Here is Marin Alsop conducting the Sao Paulo Orchestra with the final six minutes of ‘The Prodigal Son’ ballet, the section called ‘The Return’, with music by Sergei Prokofiev.

Thanks for listening.

H

That was Marin Alsop conducting the Sao Paulo Orchestra with the final six minutes of ‘The Prodigal Son’ ballet with music by Sergei Prokofiev.

Ok, some quick credits.

There was one book that was invaluable in preparing this episode. It is called ‘Natasha’s Dance’ by the historian Orlando Figes (FY-jez) spelt F I G E S. It is still available I think and is a brilliant cultural history of Russia. If you like that sort of thing.

And pretty much all the recordings in the show came from a Warner Music CD box set just called ‘Ballets Russes’. I am amazed and grateful record companies are still making these things.

Thanks for your time and I look forward to playing you some more incredible music on the next ‘Classical For Everyone’. This podcast is made with Audacity Software for editing, Wikipedia for Research, Claude for Artificial Intelligence and Apple, Sennheiser, Sony, Rode and Logitech for hardware… The music played is licensed through AMCOS / APRA. Classical For Everyone is a production of Mending Wall Studios and began life on Radio 2BBB in Bellingen NSW, Australia thanks to the incredible Mr Jeffrey Sanders. The producers do not receive any gifts or support of any kind from any organisation or individual mentioned in the show.

And here is a little more music for you. Just a tiny bit more from Igor Stravinsky… The Dance of The Firebird. Here is Seiji Ozawa with the Boston Symphony Orchestra.

Thanks again for listening.