Handel… A very German Italian Englishman. Part One.

I hope you’re in the mood for some truly beautiful music… much of it involving singing. I don’t know if I can convert anyone to the delights of early 18th century opera but the songs I’m going to play you in this episode are I think some of the most exquisite ever written. Handel was born in 1685 in Halle near Leipzig in what is now north-eastern Germany and died in London in 1759. By the time he died he was not just the most successful composer in Great Britain… he was one of the most successful people in the nation. And here is a little quote generated by Claude whilst I was researching this show. It is I think a pretty good summary of why Handel’s music has persisted for three centuries… ‘The music combines German rigour, Italian lyricism, and English choral traditions into a distinctive, accessible style characterised by memorable melodies, dramatic contrasts, and psychological insight.’

And here is a link to a playlist on Spotify with the music in this episode:

https://open.spotify.com/playlist/22bgIrrMNSxkf9MxQCBojX?si=4680d49138ed484f

The Music

The Words

Hello everyone. Welcome to another episode of the ‘Classical For Everyone’ Podcast… five hundred years of incredible music. My name is Peter Cudlipp and… If you enjoy any music at all then I’m convinced you can enjoy classical music. All you need are ears. No expertise is necessary. If you’ve ever been curious about classical music… or explored it for a while once upon a time… or just quietly wondered what all the fuss was about… then this is the podcast is for you.

And because there’s a lot of music out there each episode has something of a theme. And for this one it is the music of Georg Friedrich Handel.

I hope you are in the mood for some truly beautiful music… much of it involving singing. I don’t know if I can convert anyone to the delights of early 18th century opera but the songs I’m going to play you in this episode are I think some of the most exquisite ever written.

Handel was born in 1685 in Halle near Leipzig in what is now north-Eastern Germany and died in London in 1759. By the time he died he was not just the most successful composer in Great Britain… he was one of the most successful people in the nation. And as this episode progresses I hope the title I chose… “Handel… A very German Italian Englishman” will make some sense.

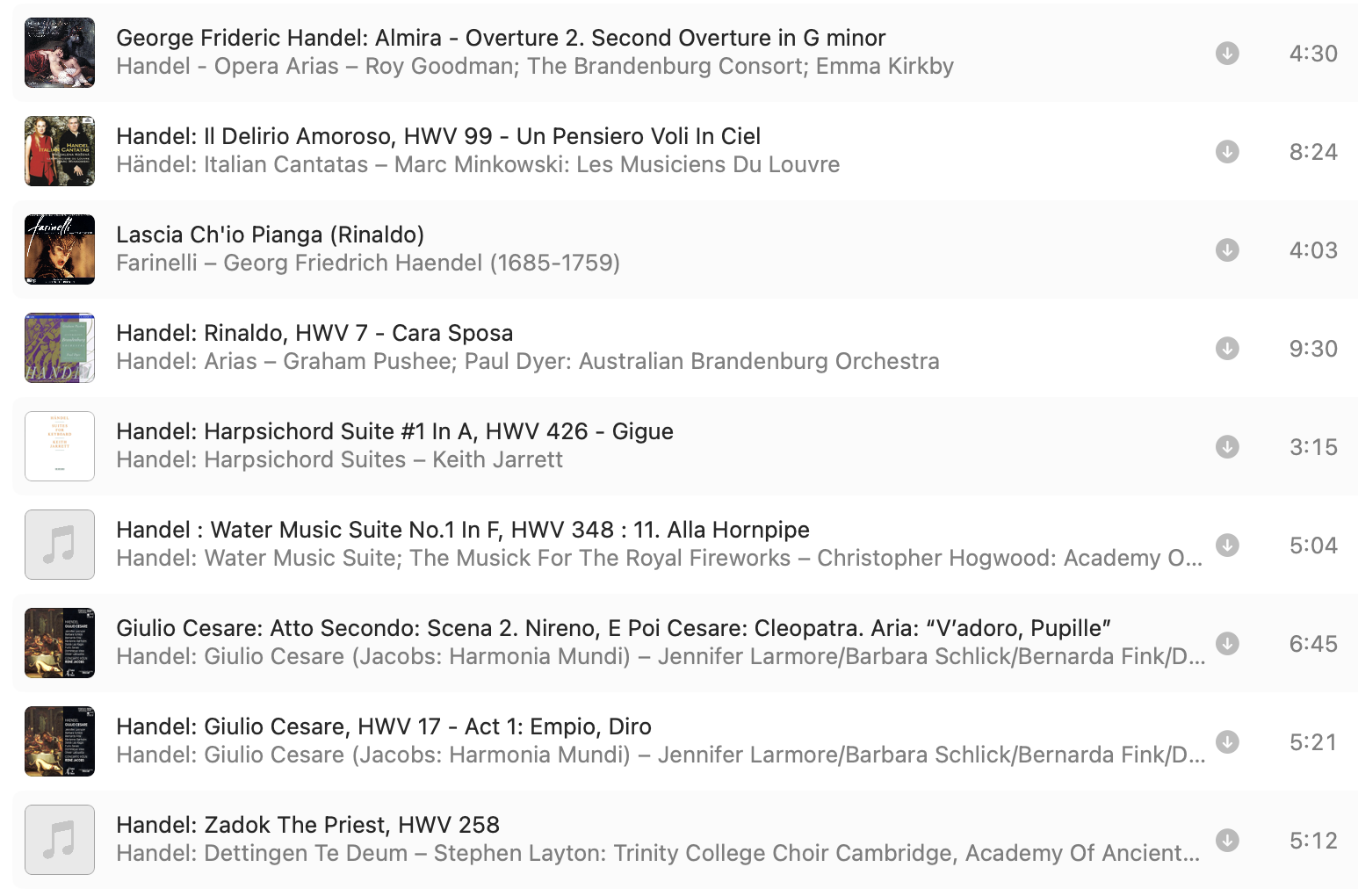

I’ll give some more biography as we go along but first some music. Here is the overture to Handel’s first opera, ‘Almira, Queen of Castile’. It was first performed in 1705 in Hamburg where Handel was employed as a violinist and harpsichord player. The theatre apparently had been let down by a more established composer who seems to have vanished pursued by creditors so Handel was asked if he could whip something up. He was 19.

The overture is about 4 minutes long and here it is performed by the Brandenburg Consort directed by Roy Goodman.

A

That was the overture to Handel’s first opera, ‘Almira, Queen of Castile’. And it was performed by the Brandenburg Consort directed by Roy Goodman.

Ok a bit more about the life of Georg Friedrich Handel. One of the stories that turns up in CD liner notes and concert programme guides is that Handel’s father actively discouraged him from pursuing a career in music. This is pretty unlikely as his father who was 28 years older than Handel’s mother, died when Handel was eleven. Fortunately this did not result in an economic catastrophe. It seems the family was able to continue with stability and Handel’s mother Dorothea would live another 34 years dying at the age of 79… old enough to have witnessed her son’s international success.

Ok. So after his time in Hamburg, where he wrote another three operas after ‘Almira’ Handel set off for Italy, where he would spend nearly four years traveling between Florence, Rome, Venice, and Naples. During this transformative period, he absorbed the Italian musical language and established connections with the leading musicians and patrons of the day, including the violinist/composer Arcangelo Corelli and the composer Alessandro Scarlatti.

As I was pulling this episode together I was imagining making a general comment about Italy being the required ‘finishing school’ for composers at this time but neither of Handel’s leading contemporaries, Telemann and J S Bach ever went there. So it must be a little more nuanced.

I think it is all about opera. Based on Handel launching himself into this genre successfully as a teenager and the fact that opera sung in Italian was what was demanded in all of the courts of Europe (except perhaps France) it makes sense that Italy was the place to go to be closest to the source. But as he was essentially a young freelance performer / composer; and opera commissions were few and far between, he composed prolifically in multiple genres.

And rather than play an excerpt from an opera (as there are more coming up later in the show) here is a section to a song cycle he wrote in 1708 for soprano and small orchestra called ‘Il Delirio Amoroso" or ‘The Delirium of Love’. A shepherdess sings to her dead lover ‘’Un Pensiero voli in Ciel’… or ‘Let a thought soar up to the sky’. Magdalena Kožená is the singer and Marc Minkowski conducts the Musicians of the Louvre. And the solo violin is played by Anton Steck. It is about 8 minutes long.

B

That was the singer Magdalena Kožená and Marc Minkowski conducted the Musicians of the Louvre, the solo violin was played by Anton Steck. And they were performing the song ‘’Un Pensiero voli in Ciel’… or ‘Let a thought soar up to the sky’

From the song cycle called ‘Il Delirio Amoroso" or ‘The Delirium of Love’ by Georg Friedrich Handel… whom this entire episode of ‘Classical For Everyone’ is about.

In 1710, after building his reputation in Italy, Handel accepted an appointment as Kapellmeister (or Head of Music) to Georg Ludwig the Elector of Hanover but almost immediately requested leave to visit London. Remember the name Georg Ludwig… he turns up again in a pretty significant role in Handel’s life. Ok. It seems likely that Handel was approached by British aristocrats whilst still in Italy. And again there is no clear information on this but whilst in London he was commissioned to write an opera to a libretto in Italianby Giacomo Rossi for the recently completed Queen’s Theatre.

Handel’s ‘Rinaldo’ became the first Italian opera specifically composed for the London stage. Based on Torquato Tasso's epic poem "Jerusalem Delivered," it is a tale of love, war and magic that follows the Christian knight Rinaldo's quest to rescue his beloved from the sorceress Armida during the First Crusade. With its dramatic sea storms, flying chariots, and magical transformations, "Rinaldo" was designed to dazzle audiences through both musical brilliance and theatrical spectacle and the opera's immediate popularity helped establish London's long-standing love affair with Italian opera and continued Handel's trajectory to become the preeminent opera composer of his day.

I’m going to play you a couple of songs from the opera. First is "Lascia ch'io pianga" (Let me weep). In this scene, Almirena, the woman Rinaldo loves is a captive of the evil sorceress and she sings…

Let me weep

over my cruel fate,

and let me sigh for

liberty.

May sorrow shatter

the chains,

of my torments

out of pity alone.

Here it is sung by the soprano Ewa Malas-Godlewska accompanied by Les Talens Lyriques directed by Christophe Rousset. It’s a pretty magical four minutes. Hope you like it.

C

That was the soprano Ewa Malas-Godlewska accompanied by Les Talens Lyriques directed by Christophe Rousset with "Lascia ch'io pianga" (Let me weep) from Georg Friedrich Handel’s opera ‘Rinaldo’.

I’m going to play you another moment from the same opera. You just heard Almirena singing at being taken from Rinaldo. Here is Rinaldo singing about the loss of Almirena…

Cara sposa, amante cara, Dove sei?Dear betrothed, dear lover,where are you?

This performance is by The Australian Brandenburg Orchestra directed by Paul Dyer and singing Rinaldo is the countertenor Graham Pushee. It is about eight minutes long.

D

That was ‘Cara sposa’ or ‘Dear Betrothed’ from Handel’s opera ‘Rinaldo’ and it was performed by The Australian Brandenburg Orchestra directed by Paul Dyer and singing Rinaldo was the countertenor Graham Pushee.

Now a few of you might be wondering a countertenor is. Well a countertenor is a male singer who is able to use a special vocal technique plus a lot of training to sing in the alto or soprano range - roughly the same pitch as a female contralto or mezzo-soprano – at volume… enough to fill an opera theatre. To put it another way, most men can speak or sing in a falsetto register… a sort of high squeaky voice. But a countertenor can make a sort of musical version of that but with much more purity, power and resonance.

And in modern productions of Handel’s operas (of which, by the way, there are over forty) and other operas of this period, the lead male roles are now frequently sung by countertenors. And why is that? Well, maybe skip ahead 30 or 60 seconds if you want to avoid hearing about a horrific surgical intervention applied to prepubescent boys that yielded some of the most celebrated singers of Handel’s age.

It is not clear when the practice of male castration was first used to prevent the beautiful singing voices of young choristers from disappearing with the onset of puberty. But it was a clandestine practice that persisted until the middle of the 1800s.

By severing the vessels that sent blood to the testicles and returned hormones; the male body would continue to mature but with several critical differences. The vocal chords would stay small and therefore the voice would retain a high register. The skin would stay smooth and childlike. The chest and lungs oddly would be enlarged and perhaps most strangely a bone structure limiting limb growth would be reduced and the castrated adult males would be much taller than the norm.

And in very rare cases the result of this brutality was a commanding figure with a cherubic face and a gloriously high voice of tremendous power. These were the ‘castrati’ and they were the operatic stars of the 1700s. They demanded huge fees, switched allegiances from composer to composer, required pieces written to their strengths and were the objects of delirious adulation. Getting one of them to appear in your opera was often the difference between success and financial ruin. And it was not just Handel who was at the mercy of these performers. Vivaldi, Gluck, Scarlatti, Monteverdi and Mozart all wrote lead roles for castrati. And the reason that those roles in contemporary productions of these operas are frequently sung by countertenors is that they can sing the high notes that were written for the castrati. Now, there is another solution to the challenge of casting of these roles and I’ll come to that in a few minutes.

But back to Handel who in February 1711 is 26 years old… and is basking in the tremendous success of ‘Rinaldo’ in London. But you might recall he had only a few months earlier accepted a job as Kapellmeister in Hanover. So he left London and went back to the job as Head of Music in a small German court. Where he was probably understandably restless. And only a year later he was back in London for the premiere of a new opera. Now he asked his employer’s permission to make the trip… which was granted… but with the explicit condition that he did not stay away for long.

Ok. Let me interrupt the adventures of young Handel with some more music. Throughout his life Handel wrote and then published solo keyboard music. Here is the closing three minute section of a keyboard suite probably written around his time in Hanover. It was published as his Suite No. 1. Here it is on a modern piano played by Keith Jarrett.

E

That was the closing section of what was published as Handel’s 1st Keyboard Suite. It was performed by Keith Jarrett.

Now we left Handel back in London in 1712 with another couple of operas on the way but with instructions to return promptly to Hanover. And these Handel disobeyed. He never went back. A year later his boss, the Elector, stopped his salary. Which makes sense. And that is where the story might have ended. But through the twists and turns of the evolution of parliamentary democracy in what eventually became the United Kingdom, there was a volatile period following the death of Queen Anne in without a direct heir in 1714. And Parliament decided the best option for keeping the country Protestant and in some distant way connected to earlier monarchs of the Stuart dynasty… was to give the throne to Prince Georg Ludwig, the Elector of Hanover. So Handel’s former boss, from whose employ he had essentially absconded, became King George I of Great Britain. This has been excellent fodder for Handel’s biographers suggesting a terrible rift that needed to be repaired before Handel’s rise to fame and fortune which benefited from royal patronage could continue. But there is no real evidence to support or to disprove this.

What is known is that in the summer of 1717 Handel wrote for the King one of his most famous collections of music. It is known as the Water Music Suite and it was a group of pieces to be played by musicians on boats on the river Thames heading upstream on a rising tide alongside the King and his entourage on the Royal Barge.

Slightly paraphrasing the Daily Courant, England’s first daily newspaper this was a grand public occasion…"the whole River in a manner was covered with boats and barges. On arriving at Chelsea, the king left his barge, then returned to it at about 11 p.m. for the return trip. The king was so pleased with Water Music that he ordered it to be repeated at least three times”

Here is the conclusion of one of the three Water Music Suites performed by the Academy of Ancient Music directed by Christorpher Hogwood.

F

That was the conclusion of one of Georg Friedrich Handel’s three Water Music Suites performed by the Academy of Ancient Music directed by Christorpher Hogwood.

Usually about now in the show I will try to let you know what is coming up on the next ‘Classical For Everyone’. Well you may have guessed from this episode’s title that there is more Handel coming. After all he is at this point in his early 30s and he would die in his mid 70’s. So, in a few days’ time Handel Part 2 will be out in the world.

But back to Part 1. From the 1720’s through to the middle of the 1730’s Handel totally dominated the world of opera in London. And Handel was way more than just the composer of the operas of which he was writing on average two a year. He was the producer / impresario as well. The rollercoaster ride of matching music, casting and staging with the fickle fashions of the upper class patrons and the opinions of the press is as dramatic as many of the plots of the operas themselves.

Of all these operas I’m going to play you two songs or arias from just one of them. It is ‘Julius Caesar’ from 1724 or ‘Giulio Cesare’ because operas had to be sung in Italian. The opera is set in Egypt and the heart of the plot is Caesar becoming smitten with Cleopatra, their love affair… and, surprisingly, a happy ending.

Here from the beginning of the 2nd Act Cleopatra sings to Caesar… ‘V’adoro, pupille saette d’amore’… ‘I adore you, dear eyes, arrows of love’ It is about 6 minutes long and this is the Concerto Cologne conducted by Rene Jacobs and Barbara Schlick sings Cleopatra.

G

That was ‘V’adoro, pupille saette d’amore’… ‘I adore you, dear eyes, arrows of love’ from Handel’s Julius Caesar. The Concerto Cologne was conducted by Rene Jacobs and Barbara Schlick sang Cleopatra.

A while back I mentioned that hiring countertenors was not the only way to solve the problem of casting the operatic roles originally written for castrati. The other way was to use female mezzo-soprano singers. These performers vocal registers mean that they can sing the notes as written. They just have to pretend to be men. Now this has had the added benefit of opening up some incredible performance and recording opportunities to gifted women whose available roles were, and are, all too frequently nurses, servants, witches and abandoned wives. As the leads in eighteenth century operas they could be princes, warriors, gods and… emperors. As in this performance, also from ‘Giulio Cesare’ by Jennifer Larmore as Caesar singing the aria ‘Empio diro, tu sei’…’Evil I say you are’ in which he rages against the cruelty of Tolomeo, the villain of the opera. Again this is Concerto Cologne conducted by Rene Jacobs.

H

That was the mezzo-soprano Jennifer Larmore singing Caesar’s ‘Empio diro, tu sei’…’Evil I say you are’ along with the Concerto Cologne conducted by Rene Jacobs from Georg Friedrich Handel’s 1724 opera ‘Giulio Cesare’.

My name is Peter Cudlipp and you have been listening to the ‘Classical for Everyone’ Podcast. I have one more piece of Handel for this episode but first I want to give you a little information that I hope you find useful… If you would like to get details of the music I’ve played please head to the website classicalforeveryone.net. That address again is classicalforeveryone.net. And on the individual episode pages of the website there are links to Spotify playlists with the full versions of most of the music played in each of the episodes. And if you want to get in touch then you can email… info@classicalforeveryone.net.

Alright, to finish this episode, the first of two on the music of Georg Friedrich Handel, I’m going to stay in the 1720s. On the death of Handel’s old boss George I in 1727, his son ascended the throne of Great Britain as King George II. And for the coronation Handel was asked to write some anthems. For one he based the words on the crowning of King Solomon from the Old Testament and they begin… ‘Zadok the Priest and Nathan the Prophet’. He wrote music that builds slowly and then unleashes the strength of an orchestra and a full choir. It has been used for the coronation of every British monarch since then including that of King Charles III in 2023.

Here is the Trinity College Choir Cambridge and the Academy of Ancient Music all conducted by Stephen Layton. Handel’s ‘Zadok The Priest’.

Thanks for listening. And I’ll be back with Handel Part 2 in a few days.

I