Forgotten Vivaldi… and the Rescue of his Music

The title of this episode is perhaps a little misleading and it certainly contains a contradiction… namely, if I have a recording, and I can play it to you, then really, is ‘forgotten’ the right adjective? But it is, I hope you’ll agree, a little catchier than… ‘music from Antonio Vivaldi that might get a bit more prominence if his set of solo violin concertos called ‘The Four Seasons’ wasn’t so extremely popular’. And as we go along, I’ll tell you a little about the remarkable journey of Vivaldi’s original handwritten scores and how surprising it is we have any of this music at all.

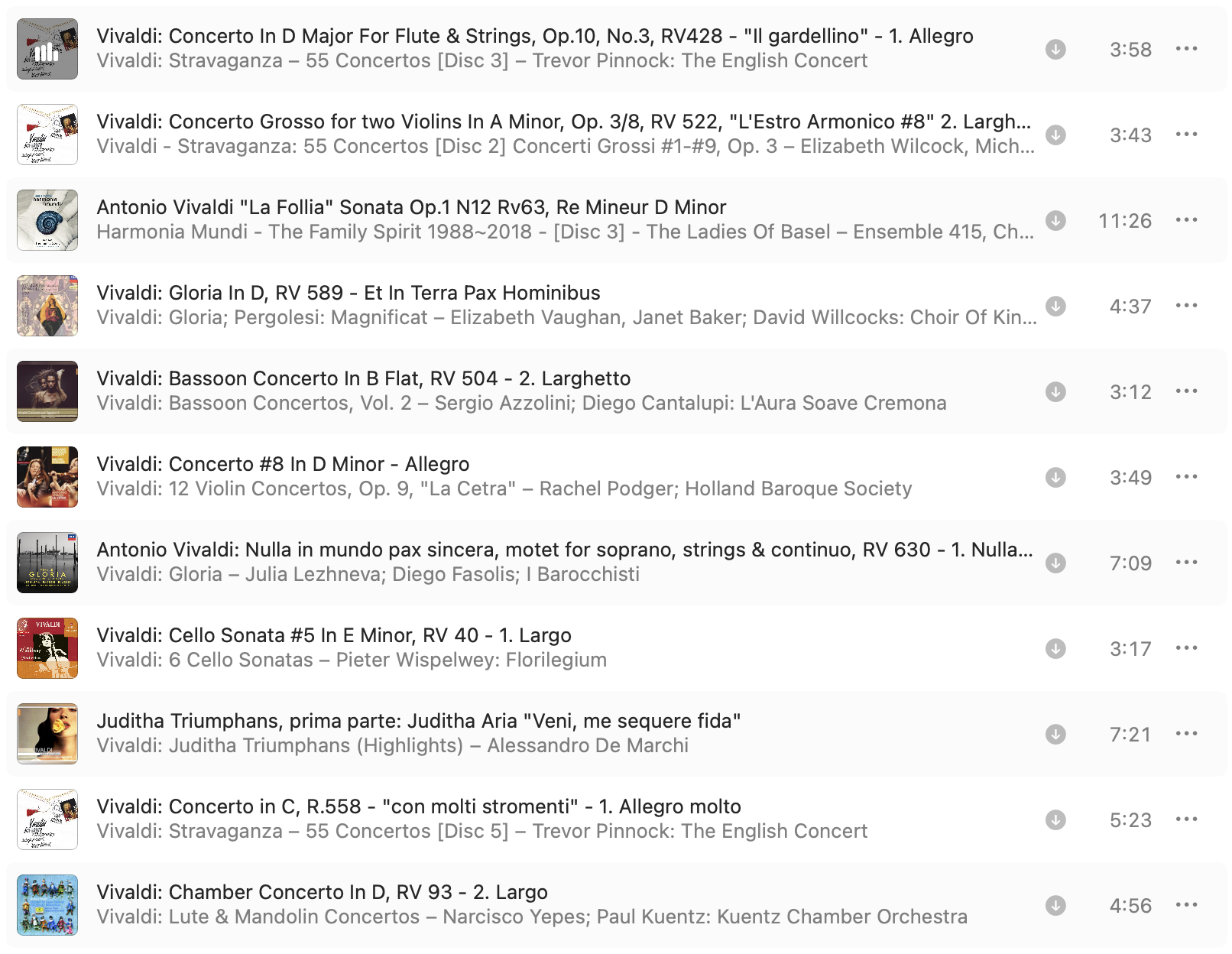

And here is a link to a playlist on Spotify with full versions of the music excerpted in this episode:

https://open.spotify.com/playlist/7BU7uciNf30thZF6yoibvc?si=09131a3e90e3441b

The Music

The Words

Hello everyone. Welcome to another episode of the ‘Classical For Everyone’ Podcast… five hundred years of incredible music. My name is Peter Cudlipp and… If you enjoy any music at all then I’m convinced you can enjoy classical music. All you need are ears. No expertise is necessary. If you’ve ever been curious about classical music… or explored it for a while once upon a time… or just quietly wondered what all the fuss was about… then this is the podcast is for you.

And because there’s a lot of music out there each episode has something of a theme. And for this one it is… Forgotten Vivaldi. Though the title is perhaps a little misleading and it certainly contains a contradiction… namely, if I have a recording, and I can play it to you, then really, is ‘forgotten’ the right adjective? But it is, I hope you’ll agree, a little catchier than… ‘music from Antonio Vivaldi that might get a bit more prominence if his set of solo violin concertos called ‘The Four Seasons’ wasn’t so extremely popular’. Another title could have been ‘The Almost Lost Vivaldi’ and as we go along, I’ll tell you a little about the remarkable journey of Vivaldi’s original handwritten autograph scores and how surprising it is we have any of this music at all

But for now, some music. This is the opening section of his Concerto for Flute and Strings with the nickname ‘il Gardellino’ or ‘The Goldfinch’. Here it is performed by the English Concert directed by Trevor Pinnock and the solo flute is played by Lisa Beznosiuk.

A

That was the opening section of Antonio Vivaldi’s Concerto for Flute and Strings with the nickname ‘il Gardellino’ or ‘The Goldfinch’. It was performed by the English Concert directed by Trevor Pinnock and the solo flute was played by Lisa Beznosiuk.

Now, because Vivaldi wrote a lot of music and as many of the titles are somewhat similar unless, like the one I just played, they received a nickname… there can be some confusion as to which is which. So for this episode I am going to give you the catalogue numbers of the pieces I play. That one was RV 428. What you might be asking is the ‘RV’ part of it? I like to think of it as ‘Recreational Vehicle’ those massive apartments on wheels that roam America’s Interstate Freeways terrorising drivers like me… as they did earlier this week in Florida.

But that has nothing to do with it. The Danish musicologist Peter Ryom put the list together in the 1970s and used the German word for list, ‘Verzeichnis’ and it became the Ryom Verzeichnis or RV list… which of was first published in French. So… a Dane listing the works of an Italian with a title in German published in French. And I will resist my English language-centric urge to say something snarky about academia and classical music and move on… quite genuinely thankful for the work that went into cataloguing Vivaldi’s works.

Next up is the slow section from the Concerto for Two Violins with the RV number 522. It comes from a collection of 12 concertos published in 1711 when Vivaldi was 33. The collection was called ‘L’estro harmonico’ which is generally translated as ‘The Harmonic Inspiration’. I’ll say a little about the term ‘concerto’ after this piece because it is going to turn up a bit in this episode. But for now listen to the beautiful entwining lines of the two violins played by Elizabeth Wilcock and Michaela Comberti with the English Concert directed by Trevor Pinnock.

B

That was the violinists Elizabeth Wilcock and Michaela Comberti with the English Concert directed by Trevor Pinnock performing the slow section of Vivaldi’s Concerto for Two Violins RV 522.

Because it is turning up multiple times today here is a quick definition of the term ‘concerto’ as it was understood in the time of Vivaldi. A concerto is a three-section work generally following a fast-slow-fast pattern in which one or more solo instruments engage in dialogue with a group of other instruments… most often a smallish orchestra. The term comes from the Latin verb concertare, meaning "to contend" or "to join together"—embodying both conflict and cooperation, as solo musicians simultaneously strive against and harmonize with a larger group. And it really was the works of Vivaldi that codified this idea of what a concerto was.

Now that credit needs to be shared with the slightly older composer Archangelo Corelli who also played a role in formalising the concerto. Another thing he and Vivaldi had in common was taking a short popular melody called in Italian ‘La Follia’ or ‘The Madness’ based apparently on a wild dance from the New World brought to Europe by the Portuguese in the 1500s; and using it as the basis for an extended display of virtuoso playing by a violin accompanied by a small ensemble.

This is Vivaldi’s version of ‘La Follia’. And here is the violinist Chiara Banchini (Bunkini) and her group Ensemble 415.

C

That was Vivaldi’s ‘La Follia’. Performed by the violinist Chiara Banchini (Bunkini) and her group Ensemble 415. It’s RV number is 63.

Alright, it might be time for a quick biography of Antonio Vivaldi. For those of you who listened to the Vivaldi episode I did back in May this is might sound a little familiar… He was born in the Republic of Venice in 1678, the son of a professional violinist who likely provided his early musical training. And based on the amount of… and the quality of… the music he wrote for the violin… he was very probably a phenomenal player. As the eldest child of a family of limited means there were not many choices available to him but after showing early musical talent it might be safe to assume that the educational opportunities afforded by the Church would lead to Vivaldi’s ordination as a priest in 1703.

But Vivaldi's career as a cleric was short-lived. He claimed ill health (possibly asthma) prevented him from saying Mass, and his most significant professional appointment also came when he began teaching music at the Ospedale della Pietà, one of Venice's renowned orphanages.

This was a home for abandoned children - foundlings, illegitimate children, and those whose families couldn't support them". It took boys and girls in separate buildings but the boys learnt trades and of the girls the ones with musical talent received lessons and most importantly… could choose to stay at the ospidale for their entire lives… becoming highly accomplished musicians and ultimately teachers themselves.

During his over three decade association with the Ospedale della Pietà, Vivaldi composed hundreds of concertos, sacred works, and other pieces for these incredible women to perform. Their concerts became famous throughout Europe, attracting distinguished visitors to Venice and helped to establish Vivaldi's reputation as a composer of exceptional skill and imagination.

In addition to his work in Venice, he travelled extensively, staging operas in various Italian cities and seeking patronage from European nobility.

By the late 1730s, changing musical tastes led to a decline in his popularity in Venice. In 1740, he sold many of his manuscripts to finance a journey to Vienna, where he hoped to secure an appointment at the imperial court of Charles VI, who admired his music.

But Emperor Charles died shortly after Vivaldi's arrival, eliminating the composer's prospects for employment. Without income or patronage, Vivaldi died in poverty in Vienna in July 1741 at the age of 63.

As a priest, writing music for essentially a convent there was going to be a demand for some sacred music. And he wrote a lot of it. Amongst his best known is a setting of the 4th century hymn ‘Gloria in excelsis deo’… maybe written around 1715… known as just Vivaldi’s Gloria. Now this really shouldn’t be in a show called ‘Forgotten Vivaldi’ but I’ll use the pretext that the second section using the words ‘Et in terra pax hominibus bonae voluntatis’… And peace on earth peace for the people of good will’.

This is David Willcocks conducting the Choir Of King's College Cambridge and Academy Of St. Martin In The Fields. ‘Et in terra pax’ from Vivaldi’s Gloria RV 589.

D

That was David Willcocks conducting the Choir Of King's College Cambridge and Academy Of St. Martin In The Fields with ‘Et in terra pax’ from Vivaldi’s Gloria RV 589.

Now that is one of many works of Vivaldi that were only rediscovered in the middle of the 20th century. And I’ll come back to that story a bit later on but for now I just want to leave you with the broader question of what happened to most of the music that was written in the 1700’s if it was not published? If it just existed in perhaps only a single complete handwritten score from which orchestral parts were made?

Ok. Another concerto. This time for the bassoon. If someone were to list the instruments for which concertos have been written in order of popularity and sheer number of compositions… I’m not sure that the bassoon wouldn’t be near the bottom. But maybe amongst the players of the orchestra of the Ospidale there was one or several performers of such skill that Vivaldi had to write concertos for them. Because he wrote 39.

And if like me, until relatively recently, you’re unpersuaded by the strange sound of the bassoon, then I hope you enjoy the older version of the instrument used in the recording I am going to play you… which I have read described as ‘warm, dark, rich, intimate, with a melancholic quality - quite different from the more refined, technically precise sound of modern bassoons.’

Here is a Sergio Azzolini playing the bassoon with Diego Cantalupi directing L'Aura Soave Cremona with the slow section from Vivaldi’s Bassoon Concerto, RV 504.

E

That was Sergio Azzolini playing the bassoon with Diego Cantalupi directing L'Aura Soave Cremona with the slow section from Vivaldi’s Bassoon Concerto RV 504.

In 1727 Vivaldi’s collection he called ‘La Cetra’ (CHE TRA) was published. Cetra means ‘lyre’ and historians think this was a way to connect his music with the instrument of the god Apollo and by implication the divine ruler of the Hapsburg empire, Charles VI to whom the set of violin concertos was dedicated. Who was apparently a huge admirer of the composer. And they would meet the following year, 1728, in Trieste where Charles was overseeing the construction of a new port.

Vivaldi gave the Emperor a copy of the score to La Cetra and an anecdote has been passed down that Charles spent more time in conversation with Vivaldi than he spoke to some of his ministers in over two years.

Here is Rachel Podger playing the violin and directing the Holland Baroque Society with the opening of the 8thConcerto in the collection and the RV number is 238.

F

That was Rachel Podger playing the violin and directing the Holland Baroque Society with the opening of the 8th Concerto in the collection ‘La Cetra’ and the RV number is 238.

After Vivaldi died his music pretty much disappeared. Which is all terribly dramatic but a few things are worth mentioning. The first of which is pretty obvious but also significant. There was no recording technology. All that was left of any music of that age was the score. Notes on some pages. And of them… very, very few were printed. Some might be copied by hand but there would certainly be many, many cases, if not the majority… where a single copy, that written by the composer, might be all that existed. That any of this music survived at all is somewhat miraculous.

Another factor was that the cultural emphasis was on new music. If you were wealthy enough to have your own orchestra or you were a bishop with a choir… then your prestige was in having new music all the time. The idea of dredging up something from a few years or a few decades earlier would only really emerge in the nineteenth century.

And only some decades later, with the rise of musicology in universities and a growing middle class with an appetite for music, would people start consciously looking for ‘old’ music.

The rediscovery of Vivaldi's music ranks among the most remarkable musical recoveries of the 20th century. The journeys of the physical scores themselves were dramas in their own right. Even though I’ve noted that the music wasn’t being performed there must have been something of a residual reputation and in the same way that wealthy collectors amassed first editions of works of literature Vivaldi’ scores must have had some value.

On his death his scores went to his brother Francesco but then a few years later they were bought by a Venetian senator, Jacopo Soranzo. In about 1780 the scores were then purchased by Count Giacomo Durazzo. They were kept in his family until in 1922 one of the Durazzo descendants bequeathed half the collection to the religious educational institution The Collegio San Carlo. Just for a moment ponder the good fortune involved in a few crates of old papers surviving in a family for a hundred and forty two years.

Six years after receiving the bequest The Collegio San Carlo needed some cash for renovations and probably unaware of what they were the custodians of, had the good sense to contact the University of Turin who sent the Professor of Music History from the university, Alberto Gentili, to have a look at what was on offer. In the words of Claude, here is what happened next…

When Gentili opened the crates that autumn, he discovered they contained autograph manuscripts by Antonio Vivaldi - roughly half of the composer's surviving legacy, including hundreds of previously unknown concertos, sacred works, and operas. This was the pivotal moment in Vivaldi's resurrection from two centuries of obscurity.

I’ll continue the adventure after some more music. Here is another seven minutes of Vivaldi’s religious music. It is a composition for soprano and small orchestra and is known by the Latin words it begins with ‘Nulla in mundo pax sincera’… ‘there is no honest peace on earth…’ Here is the opening section. The singer is Julia Lezhneva and Diego Fasolis conducts I Barocchisti.

G

That was the opening section of Vivaldi’s ‘Nulla in mundo pax sincera’… ‘there is no true peace on earth…’ The singer was Julia Lezhneva and Diego Fasolis conducted I Barocchisti. The RV number is 630.

So, back to the adventures of Vivaldi’s music. Once Professor Alberto Gentili and the University of Turin realised what they were dealing with there was problem.

Neither the university nor the city had funds to purchase the collection from The Collegio San Carlo, so they approached wealthy banker Roberto Foà, who bought the manuscripts in February 1927 in memory of his deceased infant son Mauro, and donated them to the Turin University Library.

Professor Alberto Gentili went to work on the collection. And almost immediately it became obvious that this was just a section of what had been held by the Durazzo family. And he wondered if there might be more. And so, three years later, another one of the Durazzo heirs was persuaded to part with the other half of the collection. It was purchased by another businessman, Filippo Giordano (coincidentally also in memory of a deceased son, Renzo), and donated to the University. Together, the two purchases from the Durazzos are known as the Foà-Giordano Collection - approximately 450 works in 27 volumes that now reside in the National Library of Turin.

But with that second donation, the drama was not quite over. Professor Gentili went to work on the music and just as the manuscripts were finally ready for publication and performance in 1938, Italy's Fascist racial laws forced Gentili—who was Jewish, out of his university position and into hiding for the war years.

The first public performance of any of this newly discovered music took place a year after Gentili went into hiding. In September 1939 the composer Alfredo Casella premiered six of the works, including the Gloria, at a music festival in Sienna in Tuscany. World War II had already begun but Italy would not officially enter the conflagration until June 1940. Professor Gentili survived the war dying in Milan in 1954, having lived to see Vivaldi's resurrection begin but never witnessing the full flowering of the composer's posthumous fame.

As well as hundreds of concertos Vivaldi wrote works for just pairs and small groups of instruments most of which ended up being called sonatas. The key difference from his concertos is that in his sonatas the other instruments have a more equal voice to the named solo instrument. So in the one I am going to play you which is a cello sonata, the harpsichord, organ, guitar, lute and additional cello all have more independent lines of music… or to put it another way… there is an interplay amongst a group of melodies.

Here is the opening three minutes of Vivaldi’s 6th cello sonata RV 40. Pieter Wispelwey plays the cello and the group Florilegium supplies the other instruments.

H

That was the opening of Vivaldi’s 6th Cello Sonata. Pieter Wispelwey played the cello and the group Florilegium supplied the other instruments.

To be true to the title of this episode, ‘Forgotten Vivaldi’ I should perhaps have played only music from his twenty surviving operas of the about 50 he wrote. But as a nod to that body of work I am going to play you a few minutes from an even more rare composition of Vivaldi’s. Perhaps to celebrate a naval victory in 1717 of Venice over the Ottoman Empire Vivaldi wrote what is technically called a dramatic oratorio… so like an opera but with an overt religious theme and designed for concert performance as opposed to an opera house staging. But in terms of music, ‘Juditha Triumphans’ or ‘Triumphant Judith’ is I think as good as any opera. Here is the song or aria ‘Veni, veni me sequere fida’, ‘Come, come follow me faithfully’… which Judith sings before she goes to the Assyrian camp where she will behead Holofernes and save her city. This is the Montis Regalis Academy conducted by Alessandro de Marchi. And Judith is sung by Magdalena Kǒzená. It is about 7 minutes long.

I

That was the Montis Regalis Academy conducted by Alessandro de Marchi. And Magdalena Kǒzená singing Judith’s aria ‘Come, come follow me faithfully’ from Vivaldi’s ‘Juditha Triumphans’ RV 644

My name is Peter Cudlipp and you have been listening to the ‘Classical for Everyone’ Podcast. I have another couple of pieces coming up but before I get to them I want to give you a little information that I hope you find useful… If you would like to listen to past episodes, or get details of the music I’ve played please head to the website classicalforeveryone.net. That address again is classicalforeveryone.net. And on the individual episode pages of the website there are links to Spotify playlists with the full versions of most of the music played in each of the episodes. And if you want to get in touch then you can email… info@classicalforeveryone.net.

Alright, to finish this episode I have an excerpt from another concerto. This one is slightly away from the expected structure. It is called a ‘concerto con multi strumenti’. So, rather than just one or two solo instruments there are several. Including violins, lutes and recorders. It makes for a really delightful mix and it reminds me of a lovely quote from the composer and writer Jan Swafford…

Vivaldi was not only one of the most prolific and infectious of composers, he was also responsible or some of the most productive musical ideas of his own time and was a vital influence on the next generation. And rarely has such an important artist managed to be so much fun.

Here is Trevor Pinnock with the English Concert… the opening of Antonio Vivaldi’s ‘Concerto con multi strumenti’ RV 558.

J

That was Trevor Pinnock with the English Concert… the opening of Antonio Vivaldi’s ‘Concerto con multi strumenti’ RV 558.

Thanks for your time and I look forward to playing you some more incredible music on the next ‘Classical For Everyone’. This podcast is made with Audacity Software for editing, Wikipedia for Research, Claude for Artificial Intelligence and Apple, Sennheiser, Sony, Rode and Logitech for hardware… The music played is licensed through AMCOS / APRA. Classical For Everyone is a production of Mending Wall Studios and began life on Radio 2BBB in Bellingen NSW, Australia thanks to the late, great Mr Jeffrey Sanders. The producers do not receive any gifts or support of any kind from any organisation or individual mentioned in the show. And if you have listened to the credits… here is a little more music…

This is the slow section from one of Vivaldi’s Concertos for Lute, RV 93. It has been transcribed for the guitarist Narciso Yepes and Paul Keuntz conducts his Keuntz Chamber Orchestra. And I have fond memories of this music being used in a production of Shakespeare’s ‘The Taming of The Shrew’ a very long time ago.

Thanks again for listening.

K