Beethoven's 9th Symphony

It’s Classical For Everyone’s 1st Birthday, so here’s a personal favourite. This was the first time a choir and soloists had been added to a ‘symphony’. Choral and orchestral music had been combined before but at the time there were quite rigid expectations of what a ‘symphony’ should be. That said there was a fascination amongst some parts of the Viennese audience with the way Ludwig van Beethoven seemed to be frequently tearing down traditions and replacing them with what somehow very often seemed to have been an innovation that was music’s next natural step. And with the final movement of this symphony, Beethoven took that step. Suddenly there was singing.

The Music

The Text

Hello everyone. Welcome to another episode of the ‘Classical For Everyone’ Podcast… five hundred years of incredible music. My name is Peter Cudlipp and… If you enjoy any music at all then I’m convinced you can enjoy classical music. All you need are ears. No expertise is necessary.

As this episode is being released, the podcast will be one year old. So I wanted to do something a little special. I’m going to play you what might be my favourite piece of music. It is certainly my favourite symphony. I doubt I’m alone.

A lot has been said about Ludwig van Beethoven’s Ninth symphony since its premiere in Vienna on 7th May 1824. And it could be argued that little more needs to be said today. And I do want to get to the music but first here is just a little bit of background.

Think of it as the speech at a big number birthday you have to endure before the food gets served… or the dancing starts.

Beethoven was for all intents and purposes totally deaf whilst he was writing this work and had been for close to a decade. He never heard the symphony in the way most of us are able to. I’ve been trying to imagine a comparable situation to give this some additional weight. Imagine if Pablo Picasso had been blind when he painted ‘Guernica’ and had never been able to see it.

This was the first time a choir and soloists had been added to a ‘symphony’. Choral and orchestral music had been combined before but at the time there were quite rigid expectations of what a symphony could be. That said there was a fascination amongst some parts of the Viennese audience with the way Beethoven seemed to be frequently tearing down traditions and replacing them with what somehow very often seemed to have been an innovation that was music’s next natural step. And with the final section, or movement, of this symphony Beethoven took that step. Suddenly there was singing.

Beethoven had wanted to add music to Friedrich Schiller’s 1785 poem ‘An die Freude’ or in English ‘Ode to Joy’ from as early as shortly after it was first published when Beethoven was a teenager . He kept coming back to it but it was only with his final symphony that he was able to finally combine the words with his music.

And because the words are generally sung in German I think it is reasonable to say that for English speaking audiences they are sometimes not quite given the weight they deserve.

I want to talk about the poem for a minute and then one critical thing Beethoven did with it.

First, let me ask you to consider that the German word ‘Freude’ from the title of the poem ‘An die Freude’ had and, I guess, still has a broader meaning than the general understanding of the English word ‘joy’ from the English translation of the title… ‘Ode To Joy’. Joy is I think a word used in a generally personal, individual sense. ‘I felt joy when I saw that child laughing’. But Freude has the idea of a sense of attachment to something greater than oneself. There is more of a spiritual state of collective transcendence supported by a certain intense vitality. And this is borne out by phrases in the poem… ‘schöner Götterfunken’ …beautiful spark of divinity… “Deine Zauber binden wieder”, …your magic binds us together… and ‘Wir betreten feuertrunken, …we enter drunk with fire.

It has become a little fashionable of late to talk about the need to reconnect with feelings of ‘awe’… as in the word ‘A W E’. To see things that are far greater than us as individuals. In that sense I think ‘Freude’ has an interesting contemporary currency.

But In one critical sense though, the poem is showing its age. It is quite fairly considered to be a plea for equality produced in a society where this was a dangerous and revolutionary idea. And the line most quoted for this and then grafted by writers and critics onto Beethoven’s political outlook, is ‘Alle Menschen werden Brüder,” ‘All people will be Brothers’. You can do some special pleading that the term ‘Brüder’ was used to include both men and women. But that really only attracts attention to the problem. The intellectual movement of which Schiller was a leader, and which certainly inspired Beethoven, wanted equality for all men. Women didn’t explicitly make it into the picture. Perhaps those intellectuals of the Enlightenment thought half the population would be far too busy cooking and breeding to be troubled by such issues.

Ok. One final observation. I mentioned I wanted to touch on one aspect of the way Beethoven treated the words. Now this might have been in the programme notes for various performances I’ve heard over the years but if so it didn’t quite click. The first words that are sung are… O Freunde, nicht diese Töne! Which is ‘Oh friends, not these sounds’ and in English the sung text continues… ‘But rather let us begin more pleasing and more joyful ones’.

Now, this extraordinary moment of a deep male voice suddenly singing out three quarters of the way through a massively long symphony has so much power to it that I for one have missed what I think is some quite deliberate humour. From Beethoven. Because these are words Beethoven himself wrote and added before beginning the Schiller poem. A voice is singing out ‘Oh friends, not these sounds’. In other words, ‘Sorry about those first fifty five minutes; and then ‘I think you’ll like the next bit a whole lot more’. A composer who I’d argue must have known the astonishing power and beauty of the first three movements is I think saying… ‘you ain’t heard nothin’ yet’. How right he was.

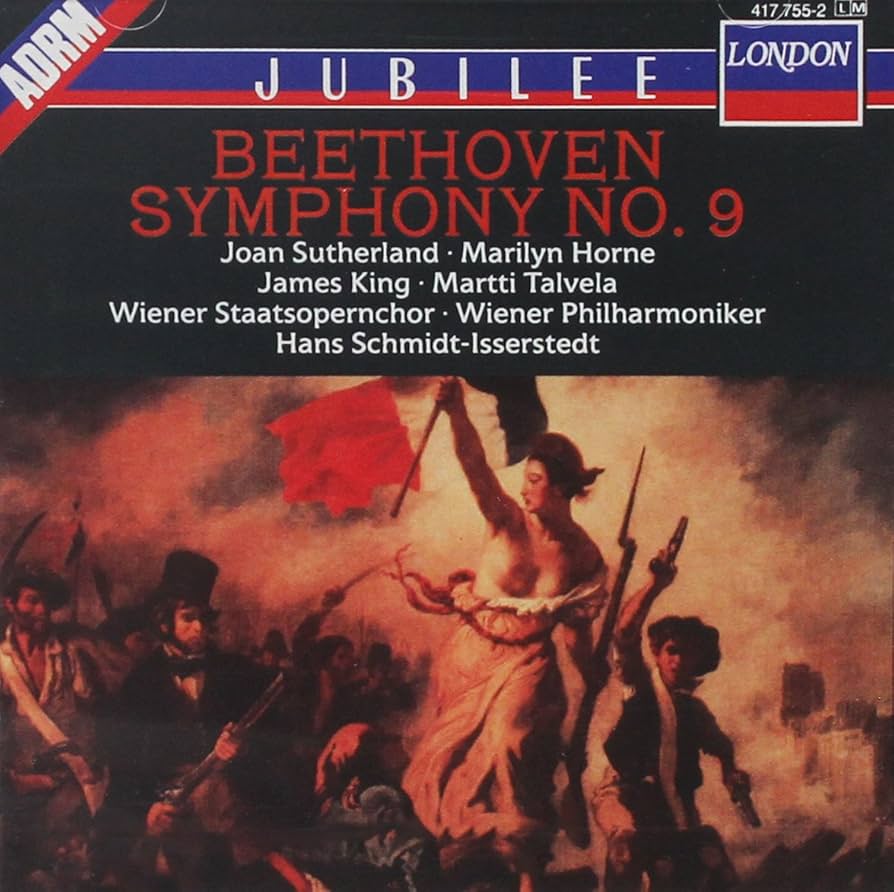

Now, please enjoy this performance of Ludwig van Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony the ‘choral’ symphony. The orchestra is the Vienna Philharmonic, the choir is the Vienna State Opera Chorus, the soloists are Joan Sutherland, Marilyn Horne, James King and Martti Talvela. And the conductor is Hans Schmidt-Isserstedt. It is about 69 minutes long and I hope you get the chance to turn up the volume.

A

That was Ludwig van Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, his ‘choral’ symphony. The Vienna Philharmonic, the Vienna State Opera Chorus, the soloists Joan Sutherland, Marilyn Horne, James King and Martti Talvela were conducted by Hans Schmidt-Isserstedt. Through nothing more than dumb luck that was I think the first CD recording of Beethoven’s 9th I bought. I’ve accumulated a few more over the years but that is the performance I keep coming back to. I hope you enjoyed it. Here’s one little anecdote about the recording I discovered in the last few days. A relatively unsung hero in the undertaking of electronically capturing the sounds of an orchestra, a choir and soloists… is the record producer. For the recording I just played you the producer was the conductor’s son Erik. No whiff of nepotism here… Erik Smith, as he was known professionally, was by this point in the mid 1960s already a very highly regarded Producer and his later career would include being responsible for the 180 CD complete Mozart edition of the early 1990s and recording over 90 operas. I have to say the father son partnership tied to that incredible recording moves me in quite a strange way. Fathers can be complicated animals. Let’s just leave it there.

My name is Peter Cudlipp and you have been listening to the first birthday episode of the ‘Classical for Everyone’ Podcast. Sincere thanks to everyone out there who has listened to the show, reviewed it or rated it, told a friend or a colleague about it, or most importantly, just enjoyed it. In this first year the podcast has been played in over a hundred countries which is a little humbling for me and for an idea that started at a dinner with my friend Jeff Sanders three years ago.

This podcast is made with Audacity Software for editing, Wikipedia for Research, Claude for Artificial Intelligence and Apple, Sennheiser, Sony, Rode and Logitech for hardware… The music played is licensed through AMCOS / APRA. Classical For Everyone is a production of Mending Wall Studios and began life on Radio 2BBB in Bellingen NSW, Australia. The producers do not receive any gifts or support of any kind from any organisation or individual mentioned in the show.

And if you have listened to these credits… here is a little more music for you. Emil Gilels playing the opening to Beethoven’s ‘Moonlight’ sonata. Thanks again for listening.

B